I had read Don Quixote back when I was 17, and never really thought much about it at the time. I knew it wasn’t short on accolades, like for instance being voted as the best book of all time by 100 prominent authors in 2002, but there always seemed to be more exciting and relevant modern books.

Then a few months ago I found myself watching Terry Gillam’s The Man Who Killed Don Quixote and started feeling that I had missed something important along the way. Since, as Sancho tells us, most of the book took place under a scorching sun in “Julys or Augusts”, I thought the time would be perfect to nail the ambiance.

After some research on which translation to read (and there are at least 25 English translations), I settled on Edith Grossman’s one, which is acclaimed to have of captured much more of Cervantes’s humour and wit than dryer and more academic translations. Anyway, the short of it is, after having reread Don Quixote, I’m convinced that it’s the greatest novel ever written. Below are some of the many reasons why.

Cervantes’ mastery of every literary form and genre that ever came before

In the early parts of Don Quixote, and even in the prologue, Cervantes demonstrates his knowledge of literature up to his era and begins to write a superlative example of a chivalric romance, with complimentary verses of poetry.

But after a few chapters, we quickly see that the gig is up. Having shown us he can master the old mould well, he earns the licence to break it. Unlike the flat fictions of the past, Don Quixote will not try to astound us by coming up with a clever new variation of monster. Instead we get what’s probably the first psychological novel, where we get to see characters develop before our very eyes.

The Greatest Project Ever Imagined…

When what’s outside of your books doesn’t match what’s inside of them, are your books simply untrue, or is reality broken? This tango between fiction and reality, is the central tension of the entire novel.

At one level it can be considered a commentary on the position fictions should occupy in our lives. More abstractly, it also signifies idealism versus pragmatism, but the validity of an imagined reality is relevant now more than ever thanks to a broad body of neuroscientific research that demonstrates just how constructed our realities are.

Self-Invention

Just like Cervantes broke the norms of fiction, Alonso Quijano broke the norms of his society: we have hints that he was dysfunctional according to the standards of his community. But tellingly, we know little to nothing about his previous life. His journey with us starts when he reinvents himself, through an astounding act of independence, into Don Quixote. Critics have remarked on how Don Quixote is one of the first examples of the ‘self made man’, authoring for himself a brand-new life. It’s perhaps unsurprising that some of the American founding fathers like Jefferson and Hamilton were avid readers of Cervantes. It’s not hard to imagine them relating to some parts of the novel as they tried to fashion a bold new world an ocean across from the old.

Unreliable narrator

One of Cervantes’ long running gags is that he’s not the author, since he writes fiction. But because this is reality, it’s being narrated to us by a Moorish historian named Cide Hamete Benengeli, who Cervantes assures us “was a very careful historian, and very accurate in all things”. And if that didn’t convince us, Cide Hamete the Muslim “swears as a Catholic Christian” to tell us the truth, which Cervantes assures us means roughly the same as when a Christian swears it.

However the reliability of Cide Hamete as a narrator is at times put into question, especially in the second part, when Hamete becomes a fully-fledged character, with a narratorial voice distinct from Cervantes’ own interjections.

A deeply political novel

In his fiction, Cervantes also splices in contemporary events like Spain’s wars in the Philippines and Netherlands, the place of Moors and women in 1600’s society, the role of the Church and the activities of the inquisition. The novel also features a hilarious chapter where a priest burns ‘obscene’ books in Quijano’s library, all the while knowing the raunchiest scenes in them, and sparing one of Cervantes’ earlier novels, because the “author has promise”.

Books speaking to other books

Don Quixote is really two books in one. The first part of the novel was published in 1605 and was an immediate hit. Trying to capitalise on its success, an impostor under the pseudonym Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda tried to publish a part two before Cervantes could finish it in 1615.

This created an interesting intertextual dynamic: characters from the spurious Avellaneda Don Quixote find themselves in Cervantes’ part 2, speaking to the real Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, who themselves are aware of the publication of both Cervantes’ part 1, and Avellaneda’s fake.

Timeless

There’s something about Don Quixote that transcends time and place. It’s been translated to over 140 languages, finding some measure of resonance with audiences as diverse as South American revolutionaries deep in jungles to Japanese schoolchildren. And in an age where the border between fiction and reality is as blurred as ever, or when the disparity between the world as it is and the world as we imagine it should be is as clear as ever, Don Quixote remains, 400 years later, as relevant and crisp as the day it was written.

Philosophical Multitudes

As fitting a parable as simple as knight and squire go on a road trip, the philosophical questions in this novel are ever compounding. Take for instance the most obvious one. What happens when idealism hurts good people?

In his quest to make a better world, Quixote unintentionally also does a lot of harm, hurting especially Sancho. But the world Quixote inhabits is deeply unfair and unjust, and probably the product of someone less pure but who had the determination to make his fiction the reality. And to an extent, how we organise and control societies are more often the fruit of some concocted notion than we’d like to admit.

Now it’s probable that initial readings of Don Quixote focused on the physical comedy and humour of an insane hidalgo. But later, readings of Don Quixote were often the fruits of the times it was in. Social revolutionaries saw in it for instance the notion that individuals might be right as they transverse a society that might be wrong and psychologists saw patients inhabiting a gentler, kinder world than a more sinister real one.

Quixote or Sancho?

Besides creating a novel that is easily relatable to, Cervantes also deserves praise for creating not one, but two characters everyone emphasises with. I say this because I think on some level, we all see, or would like to see, different parts of both Quixote and Sancho in us. At times we’d like to think that we are idealistic and will chase our dreams to the ends of the earth. On other occasions I think we’d like to think of ourselves as pragmatic, sensible, and endowed with the rationality to determine that if you charge a windmill, no good will probably come out of it.

Quixote redeemed through Sancho

But at a human level, I think the most emotional dynamic is how the relationship between Sancho and Quixote evolves. At first, Sancho joined Quixote on his quest in exchange for money and a promised governorship of an ‘insula’ – a Latin word he didn’t know meant island. Later in the novel it’s clear that Sancho has started caring for his master and isn’t in it just for the money, even though at times Quixote is abrasive and unkind towards him.

However Sancho finally does get his governorship, and serves with distinction, adopting such wisdom in day to day matters that the citizens of his fictional insula of Barataria “considered their governor to be a second Solomon.” In fact, he “ordained things so good that to this day they are obeyed in that village and are called The Constitution of the Great Governor Sancho Panza.” Not too shabby for an illiterate peasant from La Mancha. But Sancho only lasts as a governor 10 days, barely eating and sleeping while trying to be a good governor, before finally realising that he was happier in his life as a peasant.

It’s probable that if left to his pragmatism, Sancho would have of never left his farm. But spurred by Quixote’s idealism -falls, beatings, and explosive bowel syndrome inducing potions notwithstanding- he gets to be something greater. Alone, Quixote in his idealism is selfish. But the fact that he was the catalyst for Sancho Panza growth is the major source for Quixote’s redemption as a character.

Cervantes’ Humanism

Two of the most beautiful scenes I’ve ever encountered in literature are in the last moments of the novel. With their unnamed town in view (so all of La Mancha can claim Quioxte as their son Cide Hamete tells us), Sancho dropped to his knees and in equal measure of hilarity, tragic earthliness and sincere hope bellows out:

“Open your eyes, my beloved country, and see that your son Sancho Panza has come back to you, if not very rich, at least well-flogged. Open your arms and receive as well your son Don Quixote, who, though he returns conquered by another, returns the conqueror of himself; and, as he has told me, that is the greatest conquest anyone can desire.”

Even more moving is a scene a few chapters on, where, realising that a fully sane Alonso Quijano is on the verge of death, Sancho Panza, a character who has spent 700 pages trying to make a madman see reality, tries to prolong the life of his friend by telling him to abandon reality anew:

“Don’t die, Señor… because the greatest madness a man can commit in this life is to let himself die without anybody killing him… get up from that bed and let’s go to the countryside dressed as shepherds, just like we arranged: maybe behind some bush we’ll find Señora Doña Dulcinea disenchanted, as pretty as you please. If you’re dying of sorrow over being defeated, blame me for that and say you were toppled because I didn’t tighten Rocinante’s cinches; besides, your grace must have seen in your books of chivalry that it’s a very common thing for one knight to topple another, and for the one who’s vanquished today to be the victor tomorrow.”

And only because the novel is 800 pages long, a complete going out and coming back, does the beauty of those lines fully sink in. Alonso Quijano has learned a great deal. Sancho Panza has learned even more. And as perhaps is fitting a novel that’s about a specific something on the surface but is really about everything in its depths, we can’t really be sure of much. But I think I can be sure of what Dostoevsky meant when in his diary he wrote:

“There is nothing in life more powerful than this piece of fiction. It is still the final and the greatest expression of human thought, the most bitter irony that a human is capable of expressing; and if the world came to an end and people were asked somewhere there: ‘Well, did you understand anything about your life on earth and draw any conclusion from it?’ a person could silently hand over Don Quixote. ‘Here is my conclusion about life. Can you condemn me for it?’”

My Main Take Away from Don Quixote

Despite that, what I’ve found Don Quixote to mean to me is the realisation that our imaginations actively shape our perception of the world and our ways of interacting with it. Fiction in this sense becomes a cross dimensional sand, helping us build the sandcastles of our imagination in the sandboxes of the real world.

But more fundamentally, Cervantes’ great novel teaches us of the importance of both Quixote’s and Sancho’s in the La Mancha’s of our lives. This enables in us all a powerful resolve to be a Sancho to a Quixote and to be a Quixote to a Sancho, and perhaps, at times, to be both to ourselves.

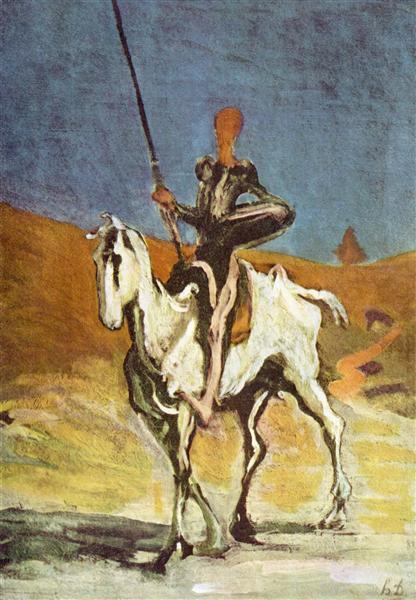

Don Quixote and Sancho Pansa - Honore Daumier